Evolution of Aircrafts: What Ancient Artifacts Reveal About Modern Aviation

What Ancient Artifacts Reveal About Aerodynamics

When aviation history is discussed, most narratives begin in 1903 with the Wright brothers and their powered aircraft at Kitty Hawk. That moment is widely recognised by institutions like the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum as the beginning of modern flight.

But the science of aerodynamics did not suddenly appear in the twentieth century.

Long before engines, wind tunnels, or aerospace engineering degrees, humans were already observing birds, airflow, balance, and lift. Archaeological artifacts from ancient Egypt and South America suggest that while early civilizations did not build aircraft, they intuitively explored shapes that align with aerodynamic principles still used in modern flight design.

I am Minhan, and I write at Readanica. This article looks at ancient flight-related artifacts through the lens of modern aerodynamics and what ancient artifacts reveal about aerodynamics, without exaggeration and without dismissing human curiosity.

The Quimbaya Gold Figurines and Basic Aircraft Stability

The Quimbaya civilization, which existed in present-day Colombia between roughly 500 and 1000 CE, produced small gold figurines often described as birds or insects. Several of these artifacts feature straight wings, symmetrical bodies, and vertical tail-like structures.

From a modern aerodynamics perspective, these features matter.

Straight wings increase lift generation by maximising airflow across the surface area. Symmetry improves lateral stability while the presence of a vertical tail-like structure is particularly notable. Vertical stabilizers are critical for yaw stability in aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles, as documented in NASA’s Flight Stability and Control studies. These are the same principles applied in modern fixed-wing aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles. Birds and insects do not possess this feature, which suggests the form is not purely biological.

Engineering tests have shown that scaled replicas of some Quimbaya figurines can glide in controlled airflow environments. This happens because lift is generated when air moves faster over the top surface than the bottom, creating a pressure difference. This does not indicate ancient aircraft technology. It simply demonstrates that aerodynamic laws are universal and independent of cultural knowledge.

Modern comparisons have made them even more fascinating. Their shape is strikingly similar to delta-wing fighter jets such as the Saab 37 Viggen, or even unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

According to the Smithsonian Institution, there is no archaeological evidence of propulsion systems, control mechanisms, or structural materials required for sustained flight. The figurines are classified as symbolic art, not functional aircraft. Still, their forms align with what modern aviation recognises as aerodynamically stable shapes.

Aerodynamic Verdict:

The Quimbaya figurines align with principles of passive aerodynamic stability but do not meet the requirements for controlled or powered flight under modern aerospace standards.

Temple of Seti I Carvings and Visual Pattern Recognition

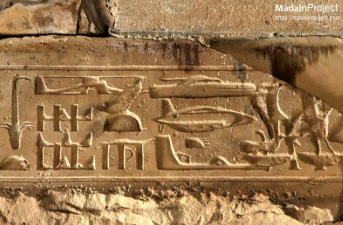

At the Temple of Seti I in Abydos, Egypt, certain carvings appear to resemble helicopters or modern aircraft when viewed in isolation. These images often circulate online in discussions about ancient aviation.

Egyptologists provide a clear explanation rooted in archaeology rather than aerodynamics.

The carvings are a palimpsest, meaning multiple layers of hieroglyphs were carved at different times. Over centuries, erosion and re-carving caused overlapping shapes to visually merge. When viewed with modern reference points, these merged shapes resemble aircraft profiles.

Aerodynamic Evaluation:

From an engineering standpoint, resemblance alone has no technical value. Modern rotary-wing aircraft, such as helicopters, rely on rotating airfoils that generate lift through blade pitch variation and angular velocity. This mechanism is governed by blade element theory, a foundational concept outlined in Leishman’s Principles of Helicopter Aerodynamics (Cambridge University Press).

The carvings at the Temple of Seti I lack the geometric continuity required for aerodynamic interpretation. The shapes often cited as helicopters do not show blade symmetry, hub structures, or airflow pathways necessary for rotary lift. Egyptological studies published by the Oriental Institute confirm that these images are palimpsests, formed by overlapping hieroglyphs from different reigns.

From an engineering standpoint, modern aerodynamics does not support interpreting these carvings as functional aircraft representations. Pattern recognition bias explains why modern observers perceive familiar machines in abstract forms, a phenomenon documented in cognitive science literature.

Aerodynamic Verdict:

The carvings do not satisfy any known aerodynamic criteria for fixed-wing or rotary-wing flight and are best understood as visual coincidence rather than technical design.

If we compare the “helicopter-like” image with today’s AH-64 Apache, the resemblance is striking: a main rotor above the body, and an elongated tail section.

Psychologists describe this effect as pareidolia, the tendency to perceive familiar objects in random patterns. Institutions like the British Museum and National Geographic agree that the Temple of Seti carvings do not represent flight technology, nor do they demonstrate knowledge of aerodynamics.

The Saqqara Bird and Lift without Power

The Saqqara Bird, discovered near Cairo and dated to around 200 BCE, is one of the most discussed artifacts in ancient flight studies. Unlike decorative bird carvings, it has flat wings and a streamlined wooden body.

Aerodynamic Evaluation:

The Saqqara Bird is the most aerodynamically relevant artifact among ancient flight objects. Its wings are flat and rigid, which aligns with modern glider design principles. Flat wings can generate lift when airflow velocity and angle of attack are sufficient, as described in NASA’s Beginner’s Guide to Aerodynamics and verified in sailplane engineering literature.

Experimental reconstructions demonstrate that the object can glide short distances. However, modern aerodynamic analysis highlights a critical limitation. Stable aircraft require longitudinal stability, typically achieved through a horizontal stabilizer. The original artifact lacks this component. Modified replicas with added tailplanes show improved glide stability, but this modification is not present in the original design.

Additionally, modern gliders rely on control surfaces to adjust roll, pitch, and yaw. The Saqqara Bird has none. Without control authority, flight cannot be sustained or directed, a principle reinforced by FAA aerodynamics manuals.

Aerodynamic Verdict:

The British Museum notes that there is no evidence the Saqqara Bird was used experimentally or mechanically. No launch systems, no repeated designs, and no written records exist. Most scholars interpret it as a symbolic object or toy that unintentionally reflects aerodynamic efficiency. The Saqqara Bird demonstrates an intuitive grasp of glide mechanics but falls short of controlled or repeatable flight by modern engineering definitions.

Related: Story of Polaris

Why Aerodynamic Shapes Appear Across Civilizations?

Modern aerospace engineering is built on principles like lift-to-drag ratio, stability, and structural balance. Interestingly, these principles can emerge intuitively.

Humans observe nature. Birds glide. Fish reduce drag. Seeds spin to slow descent. When ancient artisans shaped objects inspired by animals or motion, they often arrived at forms that align with aerodynamic efficiency.

NASA historians emphasise that controlled flight required mathematical modelling, materials science, and propulsion systems that only developed in the modern era. Ancient civilizations did not possess these tools. What they did possess was imagination, observation, and craftsmanship.

That combination explains why ancient artifacts sometimes resemble modern aircraft without implying lost technology or advanced aviation knowledge.

What Modern Aerodynamics Actually Confirms

Peer-reviewed aerospace science draws a clear boundary between aerodynamic resemblance and aeronautical capability.

Modern flight requires:

- Lift generation through airfoil geometry

- Stability through control surfaces

- Propulsion or sustained energy input

- Structural materials capable of managing stress and drag

Ancient artifacts show observational insight into form and balance, but no evidence of applied flight engineering. This distinction is critical for credibility and is consistent with consensus views from NASA, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, and academic aerospace research.

Why This Still Matters in Modern Aviation

The Wright brothers succeeded not only because of engines, but because they studied lift, drag, and control. They understood that flight depended on balance and airflow, not just power.

Ancient artifacts like the Quimbaya figurines and the Saqqara Bird show that humans were thinking about those same forces long before they could measure them. Imagination came first. Engineering followed centuries later.

This progression still defines aerospace innovation today, whether in NASA research facilities or UK aviation laboratories. Ideas begin as concepts. Concepts become designs which later become reality when science catches up.

References

Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

British Museum

National Geographic Egyptology Archives

NASA History of Aerodynamics

Encyclopaedia Britannica

American Psychological Association on Pareidolia